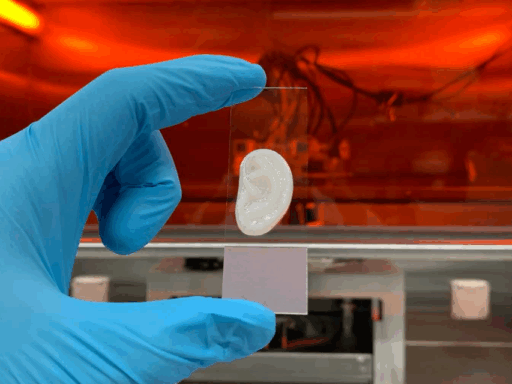

Responsible for roughly 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, traditional concrete’s heavy carbon footprint has made it a material in need of sustainable innovation. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania Responsible have offered a new solution for the cornerstone of the world’s construction. The team of engineers, materials scientists, and designers at Penn have created a 3D printed concrete that not only reduces material waste but enhances carbon dioxide capture, reports Penn Today. This innovation is a printable mix containing a sponge-like, fossil-based material derived from microscopic algae, called diatomaceous earth (DE).

“Usually, if you increase surface area or porosity, you lose strength,” said Shu Yang, co-senior author and Chair of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Penn Engineering. “But here, it was the opposite; the structure became stronger over time.”

The cutting-edge concrete, fully meeting standard strength expectations while using 60% less material, can capture up to 142% more CO₂ than conventional mixes. DE’s porous texture enables efficient CO₂ absorption and contributes to the formation of calcium carbonate while being cured, boosting durability and carbon uptake.

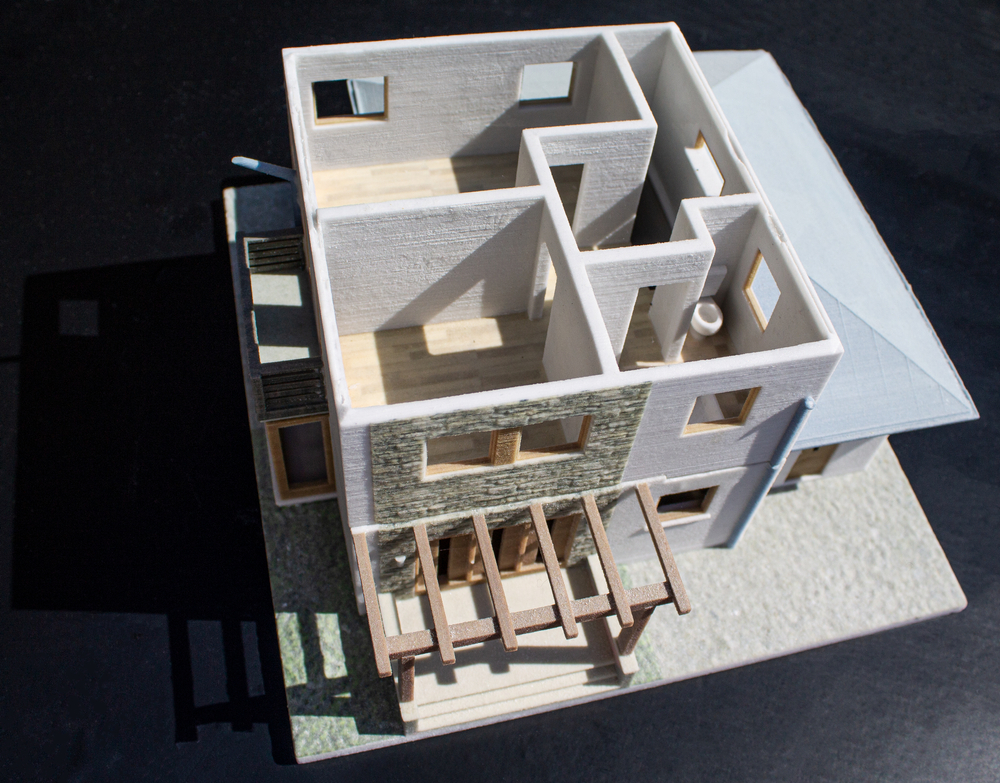

The entire project is detailed in a recent Advanced Materials study. One of the interesting aspects of this research is how the scientists also leveraged triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS), geometrically optimized structures found in coral reefs and bones – to maximize surface area while maintaining strength. “The shapes are complex, but naturally efficient,” explained Masoud Akbarzadeh, co-senior author and associate professor at the Weitzman School of Design.

The printable concrete ink was developed under the supervision of the former Penn postdoctoral researcher Kun-Hao Yu, now at Syracuse University. According to the scientist, concrete is different from conventional printing materials due to its nature of flowing smoothly, stabilizing, and only then strengthening, presenting the perfect challenge for an integrated design approach.The team keeps working to scale up to architectural elements and explore applications in marine infrastructure, such as artificial reefs and oyster beds. “The moment we stopped thinking about concrete as static and started seeing it as dynamic, as something that reacts to its environment, we opened up a whole new world of possibilities,” concluded Yang.