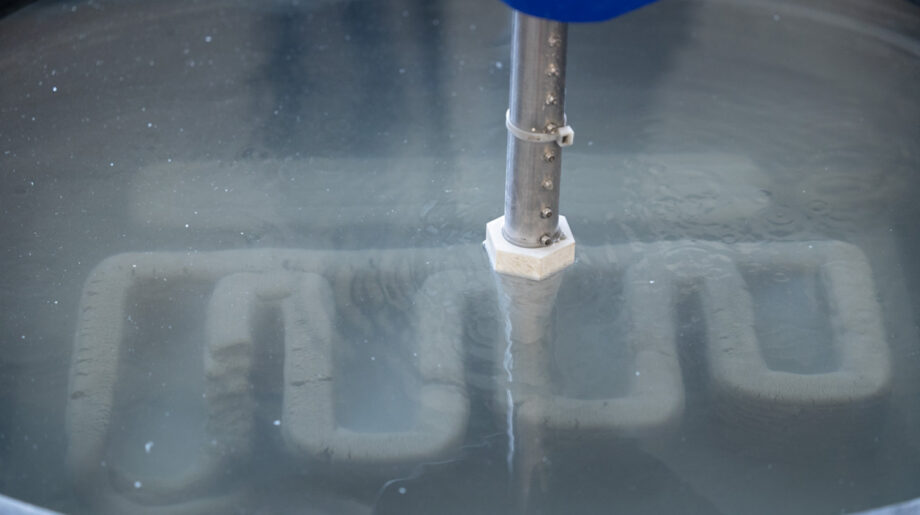

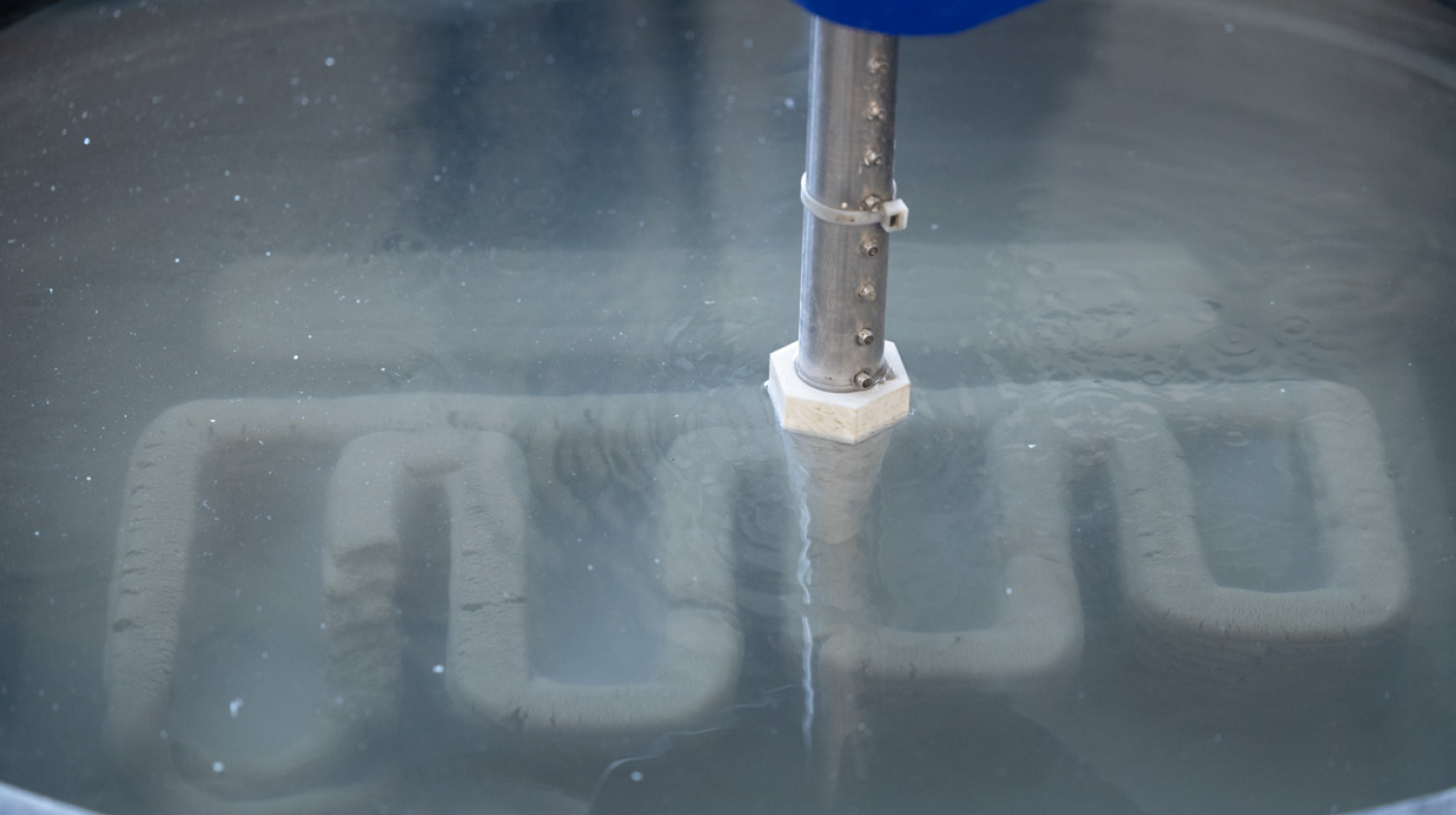

Underwater 3D printing might soon be changing the ways maritime infrastructure is built and repaired. Cornell Chronicle reports that an interdisciplinary research team at Cornell University is working on a method to 3D print concrete directly underwater. If successful, the approach could enable on-site construction with minimal disruption to marine environments.

Supervised by Sriramya Nair, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, the team is on a mission to bring large-scale 3D concrete printing to ocean settings using remotely operated vehicles instead of traditional, invasive construction methods. “We want to be constructing without being disruptive,” Nair said. “If you have a remotely operated underwater vehicle that shows up on site with minimal disturbance to the ocean, then there is a way to build smarter.”

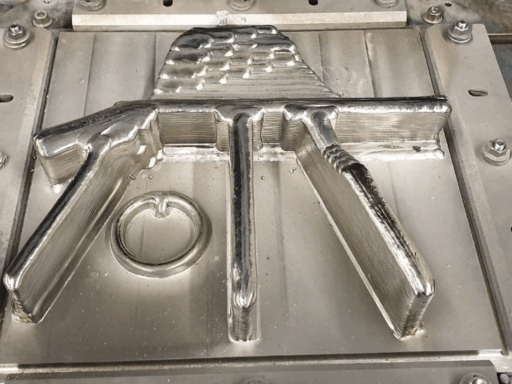

The project started in 2024, following a one-year challenge issued by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA): to develop a concrete mixture that can be deposited several meters underwater. Nair’s group was already using a roughly 6,000-pound industrial robot to print large concrete structures on land. With adjustments for prolonged exposure to water, the team discovered that underwater printing was entirely possible.

In May 2025, the project was awarded with a $1.4 million DARPA grant, contingent on hitting specific milestones. One major challenge to tackle is preventing “washout,” when cement particles disperse in water before binding. Chemical admixtures can help, but they also make the concrete harder to pump. “You’re balancing pumpability with these anti-washout agents,” Nair explained. “There are multiple parameters at play.”

DARPA added another constraint: the concrete must rely primarily on seafloor sediment, using only a small amount of cement to reduce shipping demands. In September, the team demonstrated promising results to DARPA officials. “Nobody is doing this right now,” Nair said. “This is opening up a lot of opportunities for reimagining what concrete could look like.”

The complexity of underwater 3D printing has sparked collaboration across engineering, architecture, materials science, and robotics. Electrical and computer engineering professor Nils Napp, who leads sensor development, noted the challenge of working in murky water. “Sediment is super fine, and as soon as you stir it up, you can have zero visibility,” he said.

Next up is a March competition in which teams will 3D-print an underwater concrete arch. The time is tight, but the motivation is strong. “It’s a pretty ambitious timeline,” Napp said, “and it’s cool to see so many different areas of expertise coming together quickly and pushing this forward.”